Introduction¶

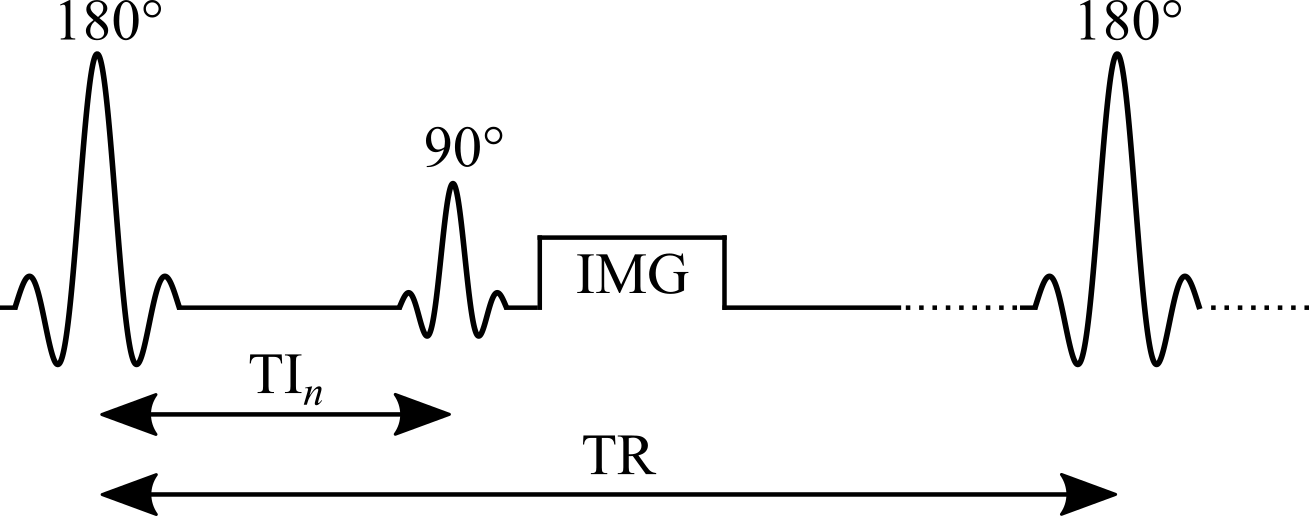

Widely considered the gold standard for T1 mapping, the inversion recovery technique estimates T1 values by fitting the signal recovery curve acquired at different delays after an inversion pulse (180°). In a typical inversion recovery experiment (Figure 1), the magnetization at thermal equilibrium is inverted using a 180° RF pulse. After the longitudinal magnetization recovers through spin-lattice relaxation for predetermined delay (“inversion time”, TI), a 90° excitation pulse is applied, followed by a readout imaging sequence (typically a spin-echo or gradient-echo readout) to create a snapshot of the longitudinal magnetization state at that TI.

Inversion recovery was first developed for NMR in the 1940s (Hahn 1949; Drain 1949), and the first T1 map was acquired using a saturation-recovery technique (90° as a preparation pulse instead of 180°) by (Pykett and Mansfield 1978). Some distinct advantages of inversion recovery are its large dynamic range of signal change and an insensitivity to pulse sequence parameter imperfections (Stikov et al. 2015). Despite its proven robustness at measuring T1, inversion recovery is scarcely used in practice, because conventional implementations require repetition times (TRs) on the order of 2 to 5 T1 (Steen et al. 1994), making it challenging to acquire whole-organ T1 maps in a clinically feasible time. Nonetheless, it is continuously used as a reference measurement during the development of new techniques, or when comparing different T1 mapping techniques, and several variations of the inversion recovery technique have been developed, making it practical for some applications (Messroghli et al. 2004; Piechnik et al. 2010).